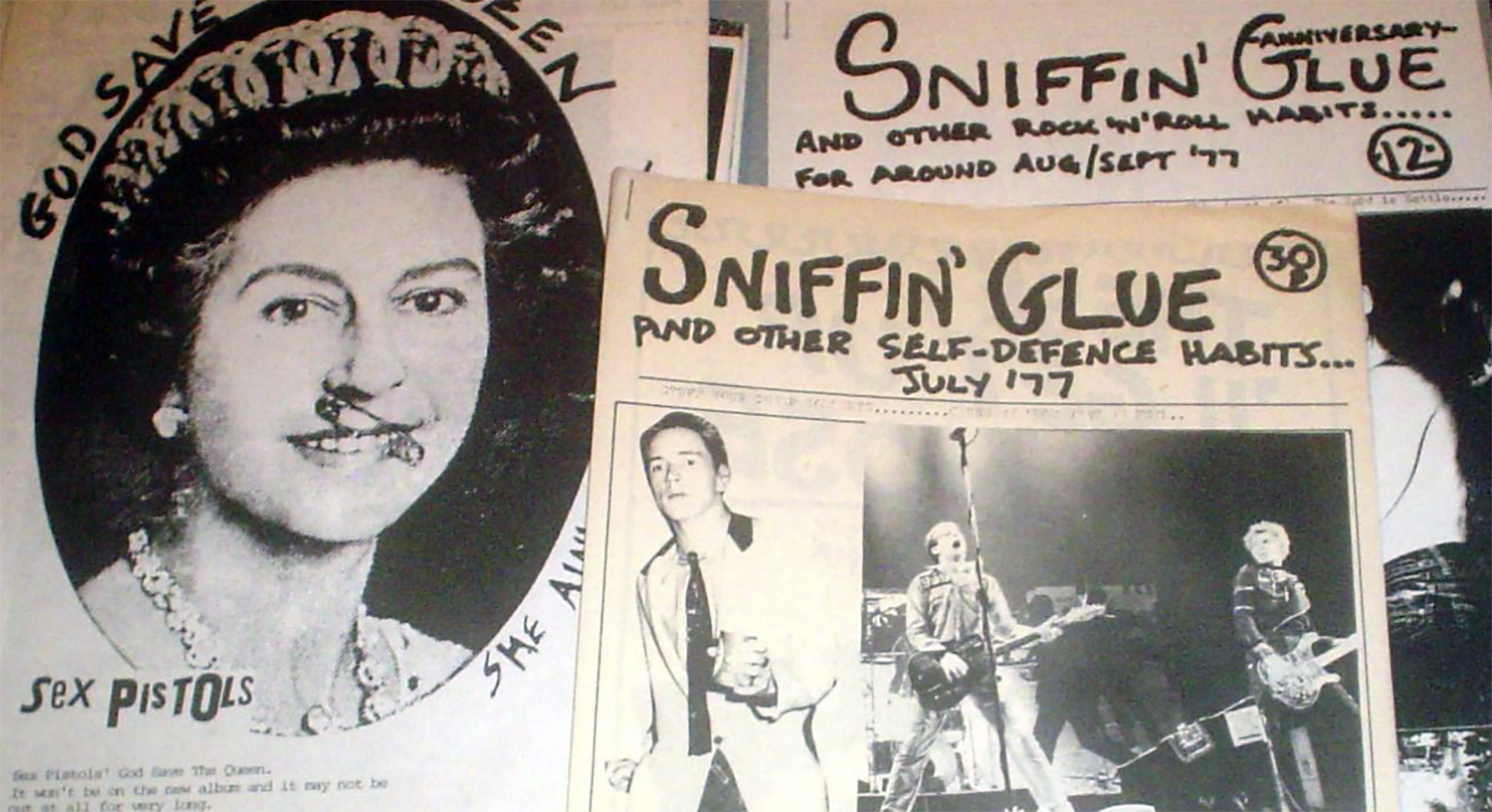

The essence of punk to me was always a sense of doing. To try without fear of failure, to use whatever you could beg, borrow or steal to make something happen, to have your voice heard. Fanzines were the epitome of this mindset. Handwritten, stapled, opinionated raw messages from the underground that took publishing and made it available to the untrained.

I was a little too young for punk at age thirteen in 1977 even though I was in London and on the King’s Road most Saturdays. I was however the perfect age to be part of the post-punk revolution within the creative industries in London in the early 1980s. As young art students at St.Martins School of Art we were filled with enthusiasm and energy, but broke. I couldn’t afford a camera, film or processing, photocopies could be accessed through the library, but were out of my price range. The £27 I received each week from my Saturday job had to pay for my weekly room and board. I used a bicycle to travel from Surrey to Covent Garden each day.

I am not asking you to get the violins out I am just outlining a reality. Nothing was easy.

Today, the tools I wanted then are available to most. Sharing platforms are free to all and unlimited image making is a given. Printing, typesetting and distribution are no longer financially unachievable thanks to online platforms and Adobe and Microsoft software.

The tools we wanted are now available. We can make music, broadcast, publish, and communicate globally. Our photographs can be seen across the world. This is big stuff, however, photographers my age seem to appreciate this more than those digital natives for whom all of this is an expectation.

Not only do they appreciate it more but they also seem to be doing more with these tools. As a teenager I was in a band that gigged regularly even though I couldn’t play the bass guitar slung around my neck. Incompetence did not stop me. I had a message and I wanted to share it through the words of The Cramps, The Dead Kennedy’s and Iggy Pop.

Photography today could embrace that punk spirit. The tools are available if the spirit is willing.

Unfortunately, I fear that everything has become safe and not safe in a good way. An obsession with technique, equipment, post production and digital perfection has seen a rise in images of conformity. Images more concerned by replicating a dominant aesthetic or subject matter than pushing the possibilities of the medium. During punk and post-punk it was important to have something to say. How you delivered that message was up to you, there were no rules of engagement, no unacceptable approach.

The vast amount of work I see today is introspective and seems to have lost that need for a message wrapping itself up in a web of influences that seem to suffocate individuality. This is a shame.

I believe that photography should say something, it should have a reason to exist. It should push boundaries and challenge the viewer. For this to happen the photographer has to be an original thinker, both in instigation and practice. Pretty pictures are fine, but they act as lift music to lull the viewer into a sense of lethargy. Punk woke up the masses, it challenged the musical form, inspired collaboration and was fun! Maybe it’s time for a bit of that punk spirit to infuse the photographic world. 2, 3 4…!

Dr. Grant Scott is the founder/curator of United Nations of Photography, a Senior Lecturer and Subject Co-ordinator: Photography at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, a working photographer, documentary filmmaker, BBC Radio contributor and the author of Professional Photography: The New Global Landscape Explained (Routledge 2014), The Essential Student Guide to Professional Photography (Routledge 2015), New Ways of Seeing: The Democratic Language of Photography (Routledge 2019). His film Do Not Bend: The Photographic Life of Bill Jay was first screened in 2018 www.donotbendfilm.com. He is the presenter of the A Photographic Life and In Search of Bill Jay podcasts.

© Grant Scott 2022

Leave a Reply to gscott2012Cancel reply