You may think that the title chosen for this article is pure click bait. It is not. It is an honest question from someone who cares about the medium.

The rejection of basic ethical considerations, tribal attitudes and mean spirited approaches to work outside of an exclusive club mentality all contribute to the sense of a medium struggling with change. That change is the democratisation of photography thanks to a thin box in everybody’s pocket.

Here are some facts. In 2021 3.2 billion images and 720,000 hours of video were shared globally online every day. On average, one person in the US captures 20.2 photos per day. Following the United States is the Asia Pacific Region, which captured 15 photos per day. Next is Latin America with 11.8 photos per day and then Africa, with 8.1 photos per day. In last place in Europe, with 4.9 photos per day. 92 million selfies will be taken daily across all devices in 2022. This number coincides with the fact that 2.3 billion photos are taken every day, 4% of which are selfies. Since Instagram was launched on October 6, 2010, there have been more than 50 billion pictures and videos shared on the platform.1.2 trillion photographs were taken worldwide in 2021. That number will increase to 1.72 trillion in 2022. By 2025, more than 2 trillion photos will be taken each year. The average user has around 2,100 photos on their smartphone in 2022.

Those facts would suggest that photography is booming, engagement with the medium is at an all time high, but I wonder how many of those people engaged with making these photographs would describe themselves as photographers?

That is the problem for photography, it is schizophrenic in nature, the photographers and the non-photographers making photographs with both sides providing their own labels to describe which team they are on. This is of course ridiculous, everyone making photographs is a photographer. But that is not the way in which I hear and see many photographers approach this situation.

You are only a photographer if you understand photography, if you know how the camera works, a camera that is not cheap or simple. When written in such blunt terms the arrogance of such a statement is clear, and yet this is the assertion that can underly many photographers understanding of what makes them different from the smartphone user. The question I ask, is why would they feel the need to take such a stance?

I think it is because photography has been taken away from those photographers, it is no longer difficult in its process of creation or dissemination and therefore the mastery of the technical is no longer a point of difference. That leaves a point of difference to be found if you wish to differentiate your practice from those whom you consider not as serious as you.

The word photography no longer means what it once meant, it is not what it once was, and although many are keen or desperate to cling to old ways of making and thinking. However, their desires will not impact on the reality of photography’s progress.

Photography is not in trouble, but the way in which it is understood and represented by some photographers could prevent its evolution, not in reality but in the meaning of the word. To understand the history of the medium and to engage in its established practices is essential to maintain and respect that history. However, to define it’s contemporary reality by that past creates a sense of exclusivity inappropriate to a democratic medium.

Photography is not in trouble, but perhaps some photographers are in their understanding of what it has become. That may be a contentious statement but if we are not able to reflect upon ourselves with honesty how can we hope to reflect the lives of others within our images with a similar sense of truth and self-awareness?

I am positive and enthusiastic about the future of photography and I am also open to what that future may be, how that word will be interpreted and what a photographer of the future will look like. I hope you are too.

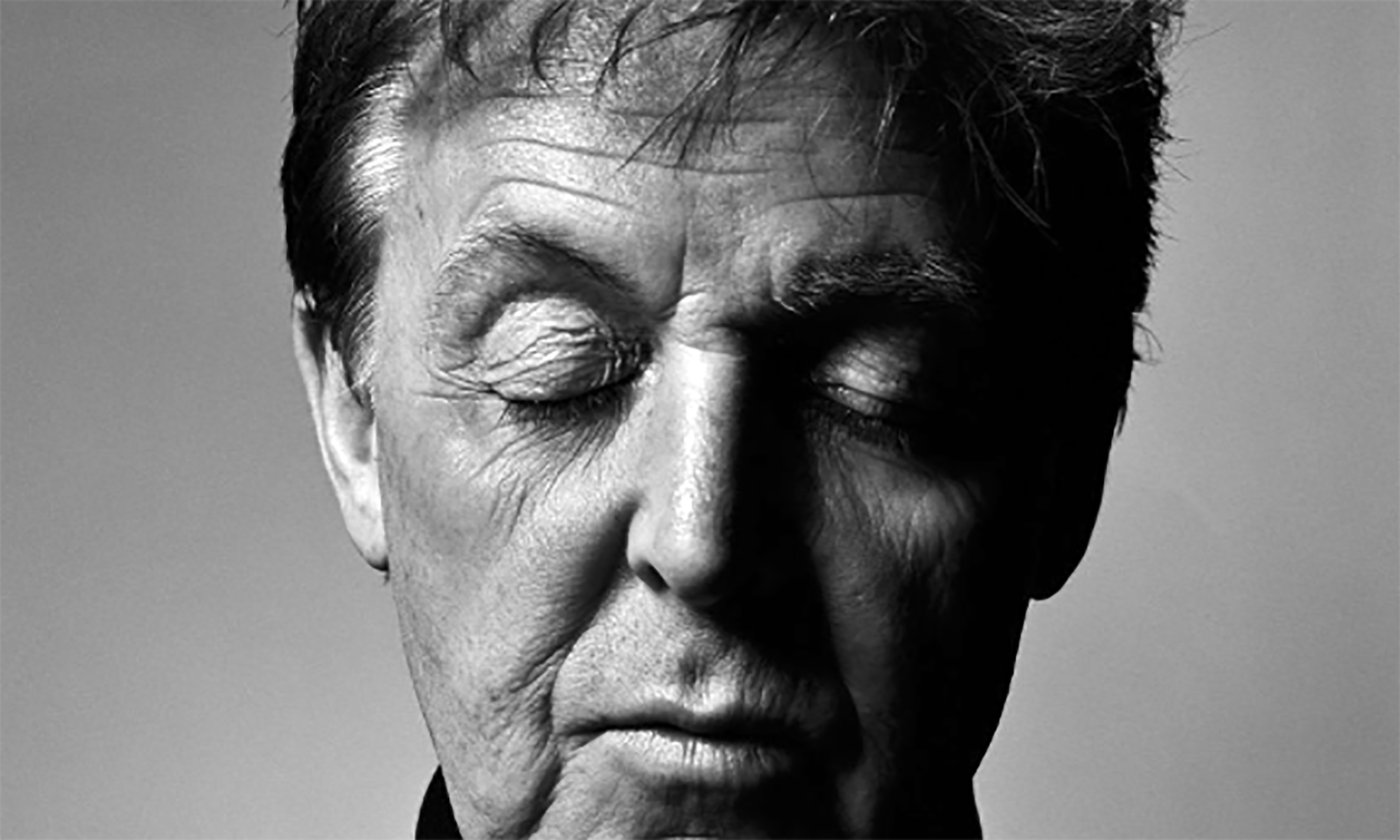

Image: Don McCullin/Imperial War Museum

Dr. Grant Scott is the founder/curator of United Nations of Photography, a Senior Lecturer and Subject Co-ordinator: Photography at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, a working photographer, documentary filmmaker, BBC Radio contributor and the author of Professional Photography: The New Global Landscape Explained (Routledge 2014), The Essential Student Guide to Professional Photography (Routledge 2015), New Ways of Seeing: The Democratic Language of Photography (Routledge 2019). His film Do Not Bend: The Photographic Life of Bill Jay was first screened in 2018 www.donotbendfilm.com. He is the presenter of the A Photographic Life and In Search of Bill Jay podcasts.

© Grant Scott 2022

Leave a Reply to Waleed AlzuhairCancel reply