The conversation online concerning the recent Vanity Fair magazine photographs by Christopher Anderson revealed an interesting misconception and misunderstanding of the photographic label ‘photojournalism’. Let me explain.

Anderson was a Magnum photographer and therefore associated with that organisation’s foundation in the history of true photojournalism. He has worked in conflict zones and made documentary work both personal and commissioned. He has also accepted commissions as a portrait photographer and produced a strong and visually interesting portfolio from these commissions.

So far, so good, I think we can agree. The truth is that Christopher Anderson is a photographer who works across a number of photographic genres with much success and a defined personal visual language. He doesn’t need to be labelled as a photographer working in only one area of practice. In a conversation with me in 2012 Anderson said this, “You know, my roots are very firmly planted within the documentary tradition. I came to photography by accident. I didn’t study to be a photographer, and I didn’t make a decision to be a documentary photographer, an art photographer or a journalist.” I think that is all we need to know about how he see’s his practice. As a photographer without labels. And yet the label of photojournalist is being pinned to his back and front in relation to his White House images by many of the misinformed ‘experts’ on social media.

This is for a few reasons it would seem in my opinion. One is based on his Magnum association, one is because of his personal work, and it would appear because his work in Vanity Fair is created to tell truth, and is unflattering and not post produced to make a ‘perfect’ world. The ill-informed seem to feel that these qualities and photojournalism are an anathma to magazine publishing and especially a magazine such as Vanity Fair. A magazine they describe as being based focused on fashion and/or lifestyle. It is neither of these. It is in fact a home for solid journalism, serious writing and sophisticated photography. However, the people getting this wrong are also those who think that editorial is a style and have no knowledge of how magazines work or how photographers are commissioned for magazines.

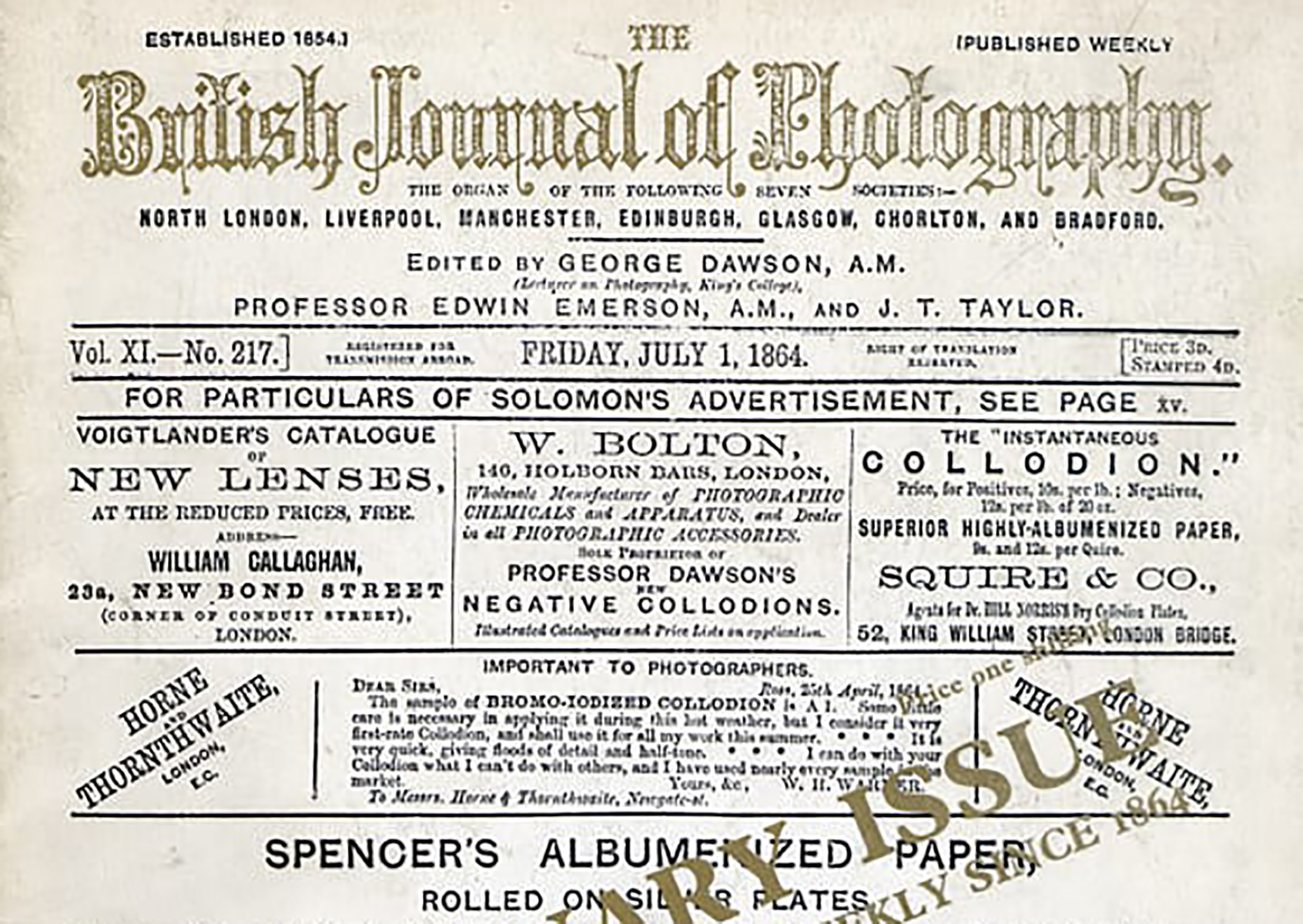

Here is some factual history for them to chew over. Photojournalism began with the first pictures of war published in newspapers during the Crimean and American Civil War. However even at this time, the image was only there to enhance the text, not lead the story. It wasn’t until the development of the smaller, lighter 35mm cameras and flashbulbs of the 1920s that a ‘Golden Age’ of Photojournalism took hold. The rise of the photo-essay and magazines such as Life, Vu and Picture Post, responded to a greater demand for images of news stories and allowed photojournalism to blossom. Better inks and papers for magazines meant full-page image spreads, allowing the image to tell the story, rather than the small engravings in the newspapers of previous decades. In short photojournalism grew out of magazines and is news based, but if you really want to get into the weeds about this I recommend checking out the writing of Helmut Gernsheim on this subject www.britannica.com/technology/photography/Photojournalism.

I have often written about the incorrect use of established photographic language by those on social media with no training or education in the history of the medium. When I have commented on this I have often been decried as being ‘stuck in the past’, ‘out of date’ or just uninformed of how the industry today works. I am none of these things as anyone who reads my writing or listens to me on the podcast will know. In fact I am often also criticised for being to positive about the present and future but correct language is important. It helps us to communicate accurately. In the same 2012 conversation Anderson told me that, “if there is a unifying thread in what I photograph – from the Haitian refugees to a war; or from my own family to Lady Gaga – it’s that I feel like I’m putting into a visual language my time on this planet.” Visual, written and spoken language are powerful forms of communication when used with understanding. This is why Anderson’s pictures have caused so much interest and discussion, he understands what he is doing.They are communicating more than just what someone is wearing or how they look. The ask us to question the decisions he has made in making them, leaving it for us to decide their message.

This is how the work should be considered, not buy putting an incorrect label on them, not by making hypotheses based on no knowledge or by deriding them because they do not comply to fake rules of composition, lighting and post-production. My suggestion is if you dont understand the terms and context, keep quiet and leave the talking to the photographer who made the work. As Anderson told me, “what I was trying to do at the time was documentary that wasn’t about running to a new situation to grab exciting, hyperbolic pictures, which would be published for their shock value. I was interested in photographing in a way which created stories which were, as closely as possible, experiences which captured as closely as possible what I was experiencing.” Exactly.

Further Reading:

https://unitednationsofphotography.com/2019/01/09/podcast-a-photographic-life-episode-37-plus-photographer-christopher-anderson/

https://unitednationsofphotography.com/2012/10/23/christopher-anderson/

https://unitednationsofphotography.com/2020/07/18/every-photographer-is-a-journalist-but-not-every-journalist-is-a-photographer/

Image: Christopher Anderson 2025

Dr.Grant Scott

After fifteen years art directing photography books and magazines such as Elle and Tatler, Scott began to work as a photographer for a number of advertising and editorial clients in 2000. Alongside his photographic career Scott has art directed numerous advertising campaigns, worked as a creative director at Sotheby’s, art directed foto8magazine, founded his own photographic gallery, edited Professional Photographer magazine and launched his own title for photographers and filmmakers Hungry Eye. He founded the United Nations of Photography in 2012, and is now a Senior Lecturer and Subject Co-ordinator: Photography at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, and a BBC Radio contributor. Scott is the author of Professional Photography: The New Global Landscape Explained (Routledge 2014), The Essential Student Guide to Professional Photography (Routledge 2015), New Ways of Seeing: The Democratic Language of Photography (Routledge 2019), and What Does Photography Mean To You? (Bluecoat Press 2020). His photography has been published in At Home With The Makers of Style (Thames & Hudson 2006), Crash Happy: A Night at The Bangers (Cafe Royal Books 2012) and Inside Vogue House: One building, seven magazines, sixty years of stories (Orphans Publishing 2024). His film Do Not Bend: The Photographic Life of Bill Jay was premiered in 2018.

© Grant Scott 2025

Leave a Reply