In episode 318 UNP founder and curator Grant Scott is in his garage reflecting on the small and big things that impact on the everyday engagement we all have with photography.

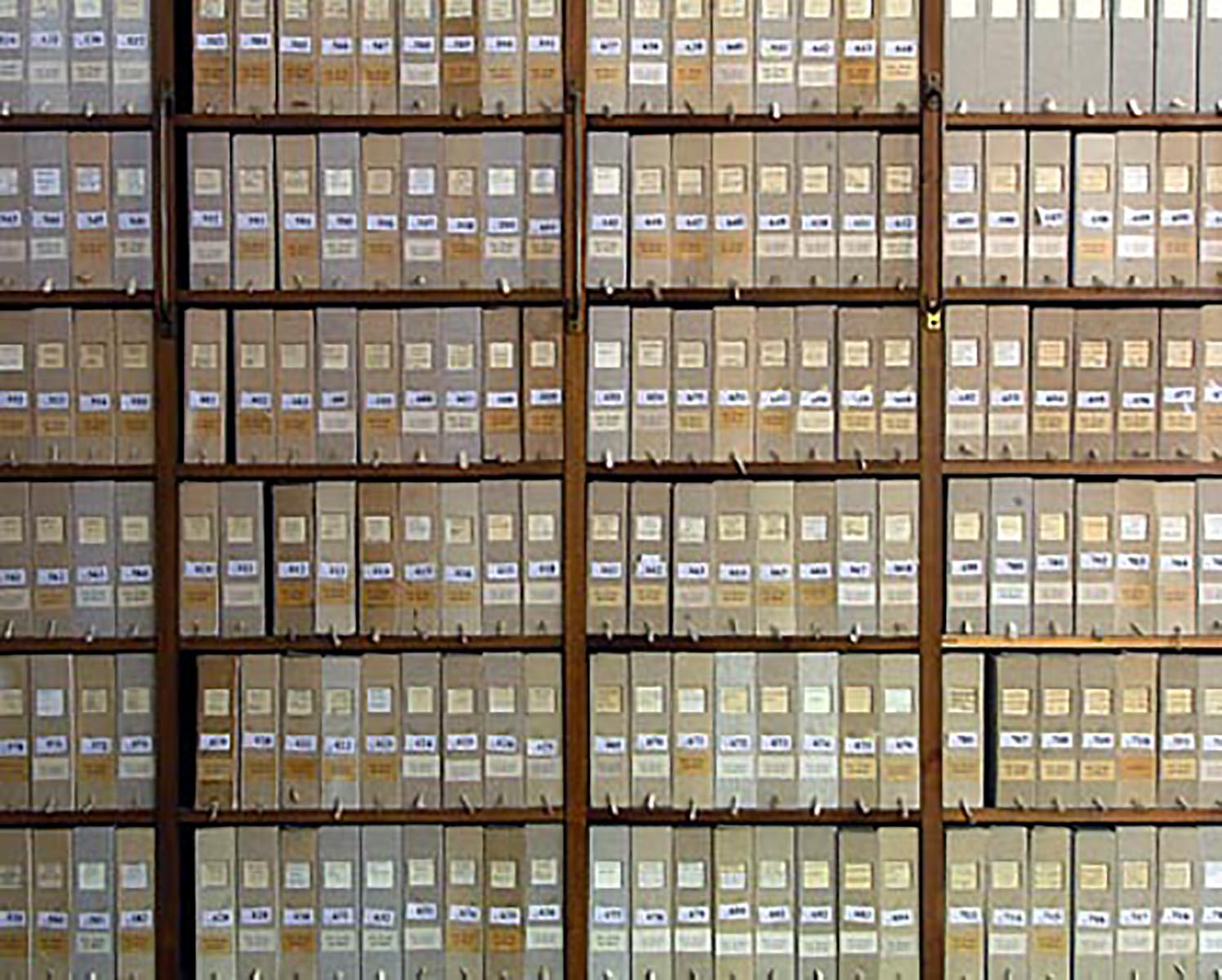

Image: © Robert Adams, Colorado Springs,1974

Mentioned in this episode:

https://fraenkelgallery.com/artists/robert-adams

https://www.uarts.edu

www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/royal-photographic-society-sell-bristol-headquarters/#:~:text=“The%20decision%20to%20sell%20RPS,mission%20of%20creating%20a%20more

Dr.Grant Scott

After fifteen years art directing photography books and magazines such as Elle and Tatler, Scott began to work as a photographer for a number of advertising and editorial clients in 2000. Alongside his photographic career Scott has art directed numerous advertising campaigns, worked as a creative director at Sotheby’s, art directed foto8magazine, founded his own photographic gallery, edited Professional Photographer magazine and launched his own title for photographers and filmmakers Hungry Eye. He founded the United Nations of Photography in 2012, and is now a Senior Lecturer and Subject Co-ordinator: Photography at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, and a BBC Radio contributor. Scott is the author of Professional Photography: The New Global Landscape Explained (Routledge 2014), The Essential Student Guide to Professional Photography (Routledge 2015), New Ways of Seeing: The Democratic Language of Photography (Routledge 2019), and What Does Photography Mean To You? (Bluecoat Press 2020). His photography has been published in At Home With The Makers of Style (Thames & Hudson 2006) and Crash Happy: A Night at The Bangers (Cafe Royal Books 2012). His film Do Not Bend: The Photographic Life of Bill Jay was premiered in 2018.

Scott’s book Inside Vogue House: One building, seven magazines, sixty years of stories, Orphans Publishing, is now on sale.

© Grant Scott 2024

Leave a Reply