You step into a small, darkened room with a dense display of violently coloured glossy photographs, and are immediately assaulted by the impression of body parts. Open mouths and thighs, hair and skin and wetness and blood – all much, much larger than life and a great deal more vivid.

But you’re not looking at bodies. These are flowers. If you stand and focus on them for a few minutes the effect wears off. Teeth and tongue become recognisable as an orchid. A rose is just a rose.

Fleurs (Flowers), 1985 / 2008

© Nobuyoshi Araki/Taka Ishii Gallery

Fleur Rondeau (Flower Rondeau), 1997,

© Nobuyoshi Araki/Taka Ishii Gallery

Feast of Angels: Sex Scenes, 1992

© Nobuyoshi Araki / Taka Ishii Gallery

The word “sensual” is over-used in photography, but it’s impossible to avoid when describing the work of Araki. Ditto “hallucinatory” and “suggestive.” But is it the images themselves that create this impression, or is it having just walked past a huge selection of the 500 books Araki has published, where nude bodies and flower parts are interchangeable?

Araki messes with your mind. I’ll come back to that again later.

This exhibition in Paris’ Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet covers 50 years of Noboyushi Araki’s work. It presents more than 400 photographs, prints and Polaroids, that massive array of books, plus a collection of 19th century Japanese prints from the museum’s permanent collection illustrating how Araki’s practice fits into classical tradition. The effect – to use yet another cliché – is sensory overload.

“Photography is life and life is a sentimental journey.” – Noboyushi Araki

The exhibition is divided into sections, some chronological, some not. Araki started photographing flowers in 1973, aged 33: the darkened room of close-up flowers that assaults the senses as you enter the exhibition dates from the 1990s and 2000s.

The next room takes a step backward. In 1971, Araki married the essayist Aoki Yoko, whom he met while he was working at an ad agency. He was 31, she was 24. Sentimental Journey is the title of a series of images of their honeymoon. They are simple black and white shots, landscape format, with minimal action or detail. Yoko appears again and again, grumpy and childlike, her eyes never looking to camera – and whether she’s nude or clothed makes no difference to the atmosphere of the pictures.

Voyage sentimental (Sentimental Journey), 1971,

© Nobuyoshi Araki/Taka Ishii Gallery

Directly following this series in the exhibition, but shot 20 years later, comes Winter Journey, another set of simple black and white images. This time, when Yoko appears, early on, she is smiling, relaxed, and looking directly into the camera. But there aren’t many pictures of Yoko. Mostly it’s the couple’s white cat, Chiro, on a scruffy balcony, or empty streets and equally empty skies. The emptiness – for which read loneliness – is palpable. There’s an abstract shot, the shadow of a tree branch against steps. In the next photograph we see the branch clearly: by a hospital bedside.

Winter Journey is the chronicle of Yoko’s death, in 1990, from ovarian cancer.

One of the last scenes is a close-up of the casket: hands place orchids around the dead woman’s body, and Chiro appears again, on a book cover placed by her head. The photograph manages to be moving and beautiful, but also shocking. Not just because of the death of this lovely and still young woman, but because of the intimacy of the image.

Winter Journey, 1990

© Nobuyoshi Araki

Intimacy is where Araki really messes with your head. The images of Winter Journey are so personal, on every level, and then you step into the next room and abruptly into the realm for which Araki is infamous: Kinbaku.

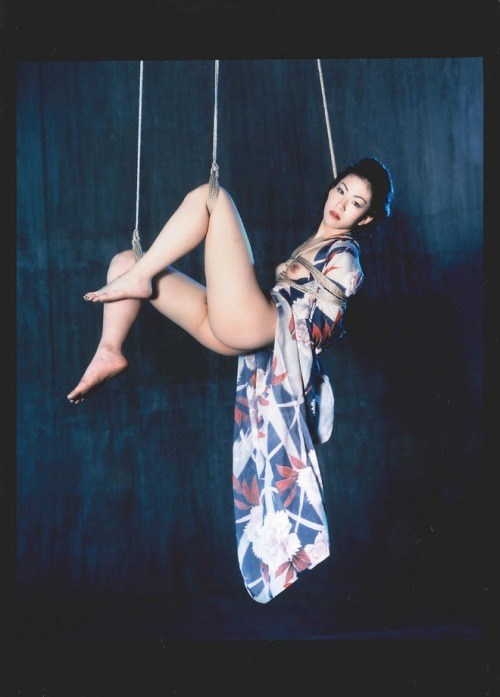

Kinbaku translates as “erotic binding,” and is a form of BDSM using rope to intricately tie up the body – a more elaborate version of using handcuffs in Western BDSM. It originated with hojojutsu, the ancient martial art of elaborately binding the hands of prisoners, and became popular in Japan in the 1950s, when specialist magazines began to publicise the practise. The 60s introduced live S&M shows involving rope bondage practiced by a Bakushi, a bondage master.

Kinbaku is very ritualised, from the kind and length of ropes involved to the way the bound body is positioned. “Asymmetric and often intentionally uncomfortable positions are employed,” according to Wikipedia. “Japanese bondage is very much about the way the rope is applied and the pleasure is more in the journey than the destination. In this way the rope becomes an extension of the nawashi’s [rope master’s] hands and is used to communicate.” The exhibition includes a quote from Araki about how he himself ties up his subjects, thus taking on the role of the nawashi.

67 Shooting Back, 2007/2008

© Nobuyoshi Araki/Taka Ishii Gallery

His critics, especially in Japan, have long denounced Araki as a pornographer, and the kinbaku images are certainly shocking: lovely young women, nude or semi-naked, are trussed up and hung up, and there are crotch shots galore. But the shock is partly because these pictures are so beautiful. The light is gorgeous, the colours are delicate. Swaddled in exotic kimono and suspended in mid-air, the girls gaze emotionlessly into the camera. They look like flowers.

When the kinbaku images are less direct, they become more disturbing. The girl looking directly into the camera appears complicit: the girl with her head down, or turned away, or cut off, is definitely objectified.

So is it art or is it offensive? Well, the next section of this exhibition includes Private Diary (1992-93) and Theatre of Love (1965): the walls are covered with scores and scores of daily pictures, of everything – traffic on bridges, people on streets, random objects on a table, and lots and lots of naked girls.

“For me, taking photographs can be just like keeping a diary. During the 1980s, everyone was taking pictures like a diary.” – Noboyushi Araki

To be honest, it gets kind of exhausting. By now, everything has started to blur together. You find yourself looking at what you think is a disembodied penis and then realising it’s an uprooted cactus. One of Araki’s milder fetishes is for plastic dinosaurs and reptiles, and you start to feel nervous when you see one – what is that thing doing there, and which body part is it heading for? As I said, Araki’s work messes with your mind.

© Ariane Nicolas / Konbini

The exhibition continues with a section of photographs with calligraphy and painting, many more naked girls, tattooed naked men, and more Chiro the cat. There is also a wall of Polaroids of the sky, taken daily since his wife’s death, in memory of her and in a kind of communication with her spirit.

“I try to imagine what the photographs taken after I die will look like.” – Araki

This is touching, but it’s not that there is anything intrinsically wonderful about any of the individual images. Instead, this section makes it clear how photography is language for Araki. Images are not icons: they are words, each one a way of putting thoughts out into the world, regardless of what those thoughts may be.

The sheer volume of Araki’s output is staggering, simply because for him photography is communication. And in the end we all hear what we want to hear, and see what we expect to see. Is it beautiful? Offensive? Disgusting? Funny? You choose.

Araki, Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet, until September 5th

© Fiona Hayes 2016

This article originally appeared on http://somethingimworkingon.tumblr.com